Introduction to Asynchronous Programming with Python's Yield Keyword

Jun 5, 2021

In this final installment of exploring Python's generators and coroutines, I'll introduce

asynchronous programming using the yield and yield from

keywords.

I'd like to note that my resource for these features was Luciano Ramalho's excellent book

called Fluent Python. At the time of this post, he is revising his First Edition to

cover more modern features of Python, like the await and async

keywords. These are what truly provides Python with its exciting asynchronous programming

feature. However, his First Edition (what I have) was written before async and

await, so asynchronous programming was introduced to me in its infancy. It shows

his incredible foresight that he had an aside at the end of the chapter which introduces

yield and yield from explaining how additional keywords would

make asynchronous programming much more explicit (and therefore easier to adapt).

Since I am not yet fluent in async and await, I'll leave a link

at the bottom to another resource which provides an excellent description of the keywords.

However, I'd like to use yield and yield from to introduce

asynchronous programming with syntax that is familiar.

First, let me introduce asynchronous programming.

Coming from C++, there are a few ways which I'm familiar with handling multiple requests at the same time (requests being messages, events, HTTP requests, etc). The simplest is just handling them serially by working through requests from a container (whether that be a queue, stack, etc). Typically in the software systems that I worked with, a very quick-lived thread would wake up and fill the container as needed. Another longer-running thread would plow through the work continuously.

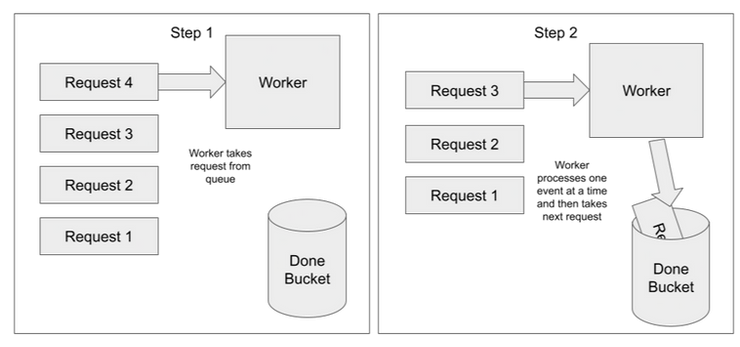

Here's a representation of this implementation with a queue:

You can see that only one request is processed at a time. Each time one is finished, it is thrown into my elegantly named "Done Bucket" and the next one is taken off the queue to be processed. This method is very simple, and no interactions between different workers must be coordinated. However, this can be slow, especially if each request can be processed somewhat independently of one another.

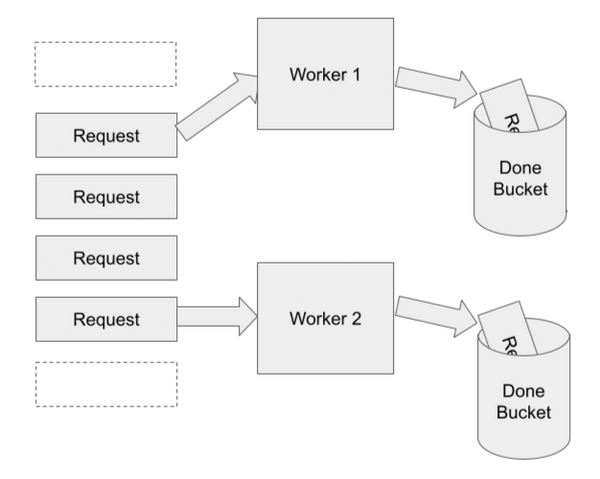

The next architecture is running multiple threads concurrently from the same shared container. This has benefits and drawbacks. Let's cover the basic case and imagine the ideal scenario. Here's how that would look:

In this case, there are two workers processing requests from both sides of the container. This means that we can process double the requests in the same amount of time, right?

Not necessarily.

In this case, the container is a shared resource between the two threads. What happens if both of them get to the last request at the same time?

Who wins?

No one. In fact, both workers will take the request out of the container at the same time, not realizing that the other has done the same. That last request will be processed twice. In some cases, this might be almost harmless. In others, it can completely nullify the important work that was done by one of the threads. This can be especially nasty if the output of the thread is actually a shared resource.

For instance, let's imagine that the request is as simple as incrementing a shared number, starting at zero. For the first iteration, Worker 1 and Worker 2 would both see the shared number as zero. Both would then output the number 1 as a result, instead of 2 as you would expect. Worker 2 nullified the work of Worker 1. In this case, the speed is simply reduced, but you can imagine more devastating results if the threads were working on databases.

To protect against this, an application can introduce mechanisms such as mutexes to ensure only one thread is working on a resource at a time. Even with these mechanisms, threading is hard, and debugging them is how I spend most of my time at work.

Note that above I chose to refer to threads as "concurrency" with the idea that these locking mechanisms prevented threads from running completely parallel to one another. The CPython interpreter also limits applications to a single thread of execution, unless using a third party module. Although the application may think it's starting multiple threads, they are actually sharing a single CPU and quickly switching contexts instead of running in parallel.

In practice (especially in C++), threads can run in parallel quite often in multi-core CPUs when they are not burdened by too many shared resources. However, I wanted to keep it separate from the third architecture that I see quite often in C++, which is parallel processing.

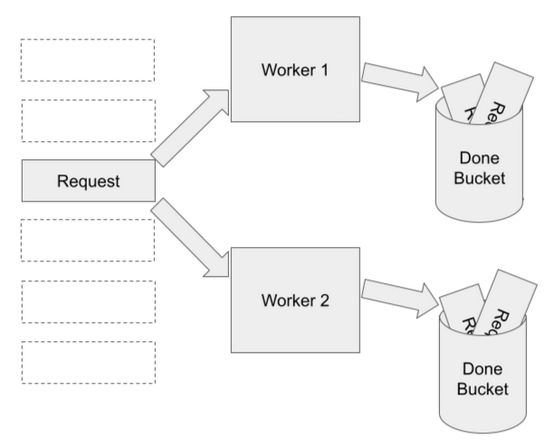

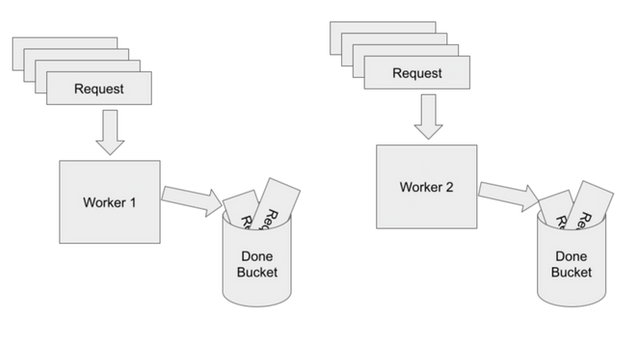

Parallel processing gets all of the benefits of multi-threading without many of the drawbacks. In this architecture, multiple independent processes execute a backlog of work in nearly isolated silos. Ideally, they can work freely without having to interact or wait for any shared resources or other processes. Here's the example from above designed using parallel processing:

In this example, each worker has its own request pile, so they can churn through the requests twice as quick as the serial example. However, when one worker reaches the end of its pile, it simply stops working. It does not need to notify the other worker or have to worry about locking the container, like in the multi-threading example.

While this seems great, parallel processing has its own challenges. Not every problem can be solved with it. It also doesn't make sense to use this architecture when the number of CPUs on your server is less than the number of things that must be processed at once (think of a internet server which might receive hundreds of requests at once - there probably aren't hundreds of CPUs available). Also, if there are requests to shared resources, this architecture will run into the same issues as multi-threading.

So which one do you choose if you need to solve a problem? It really depends on the architecture. For massive processing-heavy calculations where there are few constraints on the hardware resources (lots of memory and CPU power), parallel processing is the way to go. For simple calculations where latency is not an issue, the serial approach is probably the best bet. If latency is an issue but requests must be handled using shared or limited resources, multi- threading would usually be my choice, even knowing the risks of having to lock shared resources and tune thread priorities. Python gives a great alternative, though.

Instead of multiple threads running simultaneously with the OS as the arbitrator of which one

gets CPU time, the yield and yield from keywords allow the

application to decide when a thread of execution will change contexts. This is asynchronous

programming.

This is big.

Now, instead of needing to tune the performance of threads by changing priorities, implementing

locks, changing scheduling algorithms, etc, the application can make a section of code essentially

atomic (cannot be interrupted by the OS). After the atomic operation, then the

yield keyword changes context so that other parts of the application can execute.

Plus, because only one context is executing at a time, there is no need to lock a shared resource.

Just make sure that the context does not yield until after the shared resource has been closed.

While this may be slower than multi-threading in processing-heavy situations, it is an excellent choice for any cases where there are long waits, such as HTTP requests or large file IO. Instead of having a high-priority thread waiting for something to complete and starving all other threads, it can yield the CPU to another context until the long-running request completes. Here's an example examining the time of execution of the infamous bogosort algorithm:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

import random

import time

def counter():

''' Prints the number of elapsed seconds.

Print statements are output and rounded to the nearest second

Yield None to caller if nothing to print.

:return: None

'''

# Initialize counter - this is executed only once

start_time = time.time()

last_output = 0

# Begin counting loop - will continue forever as long as next()

# continues to be called.

while True:

# Print the current time if it has been at least one second

current_time = time.time()

if current_time - last_output > 1:

rounded_time = round(current_time - start_time)

print(f'Elapsed Time: {rounded_time}')

last_output = current_time

# If it has been less than a second since the last print

# statement, yield None back to the caller. This switches

# the context back to the caller.

else:

yield

def bogosort(unsorted_list):

''' The extremely efficient bogosort algorithm.

Sorts a list by randomly placing items at new indexes.

Attempts a single sort. If it fails and the list must be

regenerated, yields None back to the caller.

Raises StopIteration on return.

:param unsorted_list: of integers to sort

:return: Sorted list

'''

# Start endless loop. It will continue to iterate until the

# list is sorted.

while True:

# Attempt to sort list by randomly regenerating it. If it is

# sorted, return to the caller with a StopIteration Exception

sorted_list = random.sample(unsorted_list, len(unsorted_list))

if is_sorted(sorted_list):

return sorted_list

# If the list sort was unsuccessful, yield None to the caller

# before trying again. This switches context back to the

# caller between attempts so that the counter can continue

else:

yield

def is_sorted(test_list):

''' Checks whether a list is sorted

:param test_list: of integers

:return: Indicating if the list is sorted

'''

return all(

[test_list[ii] <= test_list[ii+1]

for ii in range(len(test_list)-1)])

def run_async(funcs):

''' Runs the asynchronous program.

Takes a list of generator functions as input. It schedules them

via a round-robin schedule. When one yields the execution back

this function, it schedules the next in the list until that

yields. It does not return to the start of the list until all

other functions execute.

Once one function raises StopIteration, it returns the value

from the exception

:param funcs: Containing generators

:return: Return value of first generator to raise StopIteration

'''

# Start execution loop

while True:

# Schedule functions in round-robin

for func in funcs:

# Switch context to generator

try:

next(func)

# Return value from first generator to stop iteration

except StopIteration as stop_iter:

return stop_iter.value

# Execute main function

if __name__ == '__main__':

answer = run_async((counter(), bogosort(random.choices(range(100), k=10))))

print(f'Sorted list is: {answer}')

This is a big example, so let's break it down piece by piece.

First, the bogosort algorithm is a theoretical sorting algorithm where a list is sorted by

randomly re-ordering it and then checking if it has been sorted. I've implemented this with

the bogosort() function and the random module. This example is trying to sort

a list of ten elements between 0 and 99.

A counter function maintains the amount of time which has elapsed between the start of the bogosort and the end. Since this is a random function, it can deviate wildly. Here was the output of my attempt:

Elapsed Time: 0

Elapsed Time: 1

Elapsed Time: 2

Elapsed Time: 3

Elapsed Time: 4

Elapsed Time: 5

...

Elapsed Time: 52

Elapsed Time: 53

Sorted list is: [6, 10, 35, 38, 51, 56, 61, 64, 91, 93]

It almost took a minute!

Now the cool thing about this example is the bogosort algorithm and the counter were executing

at the same time without the use of threads. That was possible because they were both generators

being driven by the run_async() function. Let's first examine

run_async().

It's actually pretty simple. It just takes a list of generators and iterates through them, calling

next() on each. When one yields, run_async() goes to the next in

a simple round-robin scheduling algorithm. After each generator has had its turn,

run_async() continues until one of the generators raises StopIteration. At this

point, it returns the value corresponding to the StopIteration exception.

The key to run_async() is that all of the generators passed into it yield

execution when they get to a point where they can safely interrupt execution. In

counter(), that's when it determines that it doesn't have anything to print

(since it's been less than a second). In bogosort(), that's when it determines

that it will have to try sorting again.

Between the yields, both methods can assume the code is atomic. If either were

writing to a shared resource (like a database), it wouldn't have to worry about the OS

automatically changing context to another thread which may completely change the resource.

Furthermore, if written correctly, there are no deadlocks, no starved threads, and you can

customize your scheduling algorithm.

I think that's pretty neat.

Now, like I said at the top, this is just an introduction into a fairly new feature of Python that

has since been expanded upon. The yield and yield from keywords

are able to introduce asynchronous programming using a fairly straightforward syntax, but

async and await are specifically designed for it. I still have

reading to do on those two keywords, but

this

is an excellent resource (and he has the same enthusiasm that I do about asynchronous programming).

I can't wait to start playing around with this feature. I've spent way too much time trying to debug multi-threading issues, and it's good to know the language designers at Python provided an alternative. Just another reason to migrate to a language that's not quite as old as I am, I guess.